For over a decade American artist Chris Anderson has devoted her art to the theme of the domestic landscape. At first glance the work conjures up paired images: architecture and nature, interior and exterior. In Anderson’s fragmented visual world, however, they unfold into dualistic topographies: random urban expansion into the undeveloped American fabric and zones of mental landscapes furnished by a wish to return to nature and the equal reality that one cannot. Motifs such as the standardized American ranch house, its token strip of lawn, and the curbside view of the house as object repeatedly revisit the work. Anderson delineates this visual horizon with the title of her Berlin exhibition: Family Stories: Historical Dislocations in the Domestic Landscape. Representing eighty paintings from a two-year Fulbright sojourn in Germany, Family Stories alludes not only to literary traditions, private biographies, and family associations, but also to movements and displacements in architectural space and time occurring beyond the sphere of individual planning and control.

Chris Anderson interprets her blueprint of daily life from personal experience: a childhood surrounded by the myths, pleasures, and banalities of rural and suburban America. She sought distance, and she came home again, in her paintings and in her domestic life. Time spent in Europe in the late 1990s gave her a vantage point from which the American Dream appeared increasingly ideal and the realities poignantly real. In Anderson’s tableaux America’s domestic landscape stands in contrast to the paranoid suburban vacui one finds behind the scenes of such work as David Lynch’s cult film Blue Velvet; rather, it emerges as a rich and complex visual montage of subtle tensions between familiar cultural patterns.

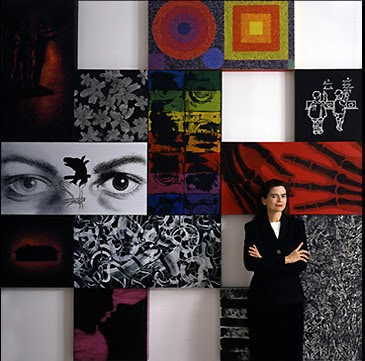

Anderson uses her paintings to build and to celebrate fantasies of the home. Paradoxically, her compositions, site specific, become the walls of a house (or a gallery). In a major installation in the Dorow Gallery, thirty-four paintings combine to create a wall-sized psychological map of Middle America. The components are standardized: squares of 53 x 53 centimeters (21 x 21 inches), or rectangles double in length in vertical or horizontal formats. With a depth of 6.5 centimeters (2.5 inches) they take on the quality of objects. The panels are arranged on the wall like dominoes or children’s building blocks. Falling short of the inevitable or logical connection between one motif and the next, the paintings recall early-American patchwork quilts stitched together from scraps of cloth—disparate, recycled remnants—or the intricate patterns of Native American beadwork. Figurative motifs are juxtaposed with the ornamental or decorative. On one hand, they provide a link to art-historical models (Frank Stella’s dynamic lines, Jackson Pollock’s allover painting, Jasper Johns’ targets, and Kasimir Malevich’s crosses). On the other hand, they are deconstructions of the mundane: ordinary patterns, flower decorations, wallpaper designs, and common home motifs.

The montage of concrete and abstract in Anderson’s work blurs the distinction between the visual codes of high and low culture in a mixture of visual models. Here everyday patterns absorb high art, and, conversely, high art incorporates popular sources rooted firmly in the Zeitgeist. Anderson’s figurative motifs draw simultaneously on myriad forms of representation: scientific illustrations (X-rays of the human body, circulatory systems, micro-organisms), ancient didactic diagrams, lovers in the pastoral twilight setting stereotypical of commercial media and advertising. A pair of eyes recurs, insistently gazing from the patchwork. The installations are punctuated by the flat, iconographic representation of the archetypal American single-family house, its pitched roof and chimney a repeated logo. The picture wall is saturated in primary colors of red, yellow, and blue. Few individual panels, however, escape the additional application of black pigment to the painting ground in a simulation of black and white photography or the tradition of grisaille.

Land in America remains abundant and affordable. In 1947, standardized American housing began on a large scale with the overnight development of Levittown. Lining the streets in repeat patterns, postwar single-family houses stand in the middle of their small lots. The new housing pattern was made famous by singer Pete Seeger with lyrics by Malvina Reynolds:

Little boxes on the hillside,

Little boxes made of ticky-tacky,

Little boxes, little boxes, little boxes,

All the same.

There’s a green one and a pink one

And a blue one and a yellow one,

And they’re all made out of ticky-tacky

And they all look just the same.

This type of building looks like the toy house on a Monopoly board: a construction kit module to be moved and arbitrarily positioned. Although the houses appear alike on the outside, all embody their own rituals of distinctiveness. In his or her home, each person strives to build a paradise, however transitory. (Postwar Germany has its own models of paradise: for example, the former housing developments for Ruhr Valley miners where scores of hardware stores catered to the home improvement market and a do-it-your-self mentality developed a prominent and even influential colloquial building style.)

In Anderson’s paintings, the house has become a constant visual sign, even an iconographic symbol. There is only one model, the single-family house with chimney projected flat on the screen of the picture plane. A chimney suggests warmth, fire, and the hearth around which the family gathers. Architectural archetype or exemplary kitsch? In his novel, The Unbearable Lightness of Being, Czech author Milan Kundera describes how kitsch moves us:

Kitsch causes two tears to flow in quick succession.

The first tear says: “How nice to see children

running on the grass!” [Happiness] The second tear says:

“How nice to be moved, together with all

mankind, by children running on the grass!” It is

the second tear that makes kitsch kitsch.

Kundera asserts that “the brotherhood of man” will be possible “only on the basis of kitsch.” Kitsch is not a timeless phenomenon, but it touches the heart of the larger society.

Chris Anderson was raised on her grandmother’s bedtime stories: the oral history of Great-great-great-great-grandmother Mary Ann and her husband Mordecai. Mary Ann belonged to the generation of American pioneers who, enduring the hardships of the wilderness, journeyed west to lay the foundations of the new states. Over two hundred years have passed since Independence Day, a landmark celebrated even in German television and media (not to mention ice cream manufacturer Schoeller, who hopes to profit with his indulgent commercials for “American Dream” Ice Cream.) After her grandmother died at the age of one hundred, Anderson inherited an unexpected treasure: a collection of numerous tiny objects, old photographs, books, and newspaper clippings. Spanning three generations—her grandmother’s, her mother’s, and her own personal collection—the archives form a private historiography. What about American life was truly significant to this family? The over 900 items of memorabilia became the basic set design for Anderson’s domestic landscapes. She was intimately connected to the documents—those from the larger world and those from the world of minutiae—their ideas, and their ideals. All became the manifestations of a cultural construct: from Mickey Mouse to Thanksgiving, from the kitchen mixer to the Bomb, from the neighborhood tree to the rocket in outer space.

Using the family archive as a point of departure, Anderson shaped a new image, or rather, a multiplicity of images. The individual components of her installations can be combined into endless configurations of variable fragments. Some become confrontational, for example, when the stark motifs of bomb, barbed wire, stick figure, teepee, house, and stars and stripes collide in black, red, blue, and white. Others, smaller arrangements of three to five components, contain light comic references to such characters as Gumby, the rubber man. The image of Gumby is integrated with pattern painting, house symbol, and Magic-Kingdom castle. Still others lay bare memories, painted in broken, discolored mélanges of brown and black. Here, in a convergence of Earth, pin-up girl, extraterrestrial, and ice-cream cone, Anderson constructs a cosmos where objects and motifs of the external world reflect the internal world or, respectively, where the internal world is revealed as mere surface. She creates an introverted and contained living environment and, in a simultaneous reversal of references, unveils a kind of cultural omnipresence. America is everywhere, from outer space to the dinner table. The powerful, the happy, and the beautiful mix with the sentimental, the pitiable, and the restless. The hunger for images and surfaces immerses the work in a flood of objects, symbols, and logos; In the span between extremes, at the seam between the paintings, crowd desires, dreams, and longings; scarcity, loss, and weariness. At some distance from the house stands a deserted director’s chair under an infinite night sky: a film director’s megalomaniacal dreams, a dreary landscape, absent actors, surreal flight. Anderson indicates no way out but to go home. Her paintings adhere persistently to their antecedents. A lack of authenticity is suddenly authenticated. Her art marks the void spaces in the given patchwork of the visual, not by merely creating something new, but by taking a fresh look at the familiar, thereby provoking reevaluation. Therein is the economy of history.

Precursors of the Berlin installations were, among others, large grisaille paintings from the late 1980s in which Anderson confronted the landscapes of nowhere-and-everywhere USA with references to European architecture and art history (for example, Masaccio’s Expulsion from Paradise). These paintings functioned as experiments to explore what lies between the cultures, and, as Anderson says, to make visible the underlying yearning for historical roots, the search for value, and the desire for cultural identity. Parallel to these figurative compositions, she created non-representational colour-field paintings whose formal language, based on the orientation of a clockface, becomes increasingly difficult to decode. We are confronted with the passage of time as an abstract order rendered emotionally experiential in colour and form.

By the time Chris Anderson was thirteen years old, she and her family had moved thirteen times. Home was a sanctuary, although a provisional and impermanent one. She later revisited the sites of her childhood, arriving just in time to see her favorite home demolished by a bulldozer to make way for a shopping mall. History appears like a runaway horse about which the most important thing becomes knowing when to jump on or off! Gumby’s strength of character lies in his ability to bounce back. The toy, quintessential acrobat, stands as a resurrection figure: here the banal and the sacred become one. Another eternal cartoon character, Mickey Mouse, provides daily elixir against the fear of loss. With the turn of the millennium, this fear has grown beyond the boundaries of cultural sublimation; it is predominantly and repeatedly existential—manifest for many in ghettoization, exclusion, poverty, social violence, ecological threats, and homelessness.

In the house, in our own homes, we find ourselves at the center of our worlds. Here is the life core from which we reach out, seeking orientation. The etymological dictionary charts the derivation and development of the German word wohnen (“to live”, “to reside”), from indo-Germanic roots. It originally signified streben nach (“to strive for”). The meaning evolved into one of gewohnt sein or zu wohnen (“to be used to” or “to dwell”); only today is the word used to mean “staying permanently in a familiar place”. In the postwar German “Economic Miracle”, the word gained conceptual cult status in the proliferation of Schöner Wohnen (“Better Living”) magazines. In Chris Anderson’s paintings, the requisite props of everyday life as objective movable scenery no longer support the concept of living and dwelling. Assembled like pieces of a puzzle or stills from a familiar film—not quite real, yet not quite alien—they reveal a symptom of dislocation woven into the domestic social fabric over decades, and perhaps over generations. Anderson’s diagnosis: spiritual homelessness.